THIS WOMAN'S WORK,

THIS WOMAN'S WORLD

Ice cream only costs $1.30 by the waterside at Boat Quay, and children clamour in the queue for their taste of heat relief. There is a youthful energy along this scenic bend of the Singapore River as children zigzag between the legs of ever watchful parents, the totems of the financial district looming along the horizon.

These precious hours of family time can mean so much to those working parents constrained by intensive weekdays.

Much of the watching is done through a lens or screen which records every movement and scene. Just for a moment, you could almost pretend Singapore is the domain of free-spirited children, instead of working professionals striving for a career in the world’s business hub.

Weekends spent together in high-traffic areas like Boat Quay are the epitome of family time in a work-driven Singapore. Photo: Angela Ho.

Weekends spent together in high-traffic areas like Boat Quay are the epitome of family time in a work-driven Singapore. Photo: Angela Ho.

These snippets of quality time are rare. The reality for many of Singapore’s working mothers is a reliance on the support of a maid to help care for their kids while they transition back into the workplace after giving birth.

Polly Kuan rose through the ranks after starting her dream career with Singapore Airlines (SIA), before 'retiring' at 24 and becoming a mother. She says the news of SIA’s shift in maternity leave policy is a cause for celebration for those kids who grew up with similar dreams to her.

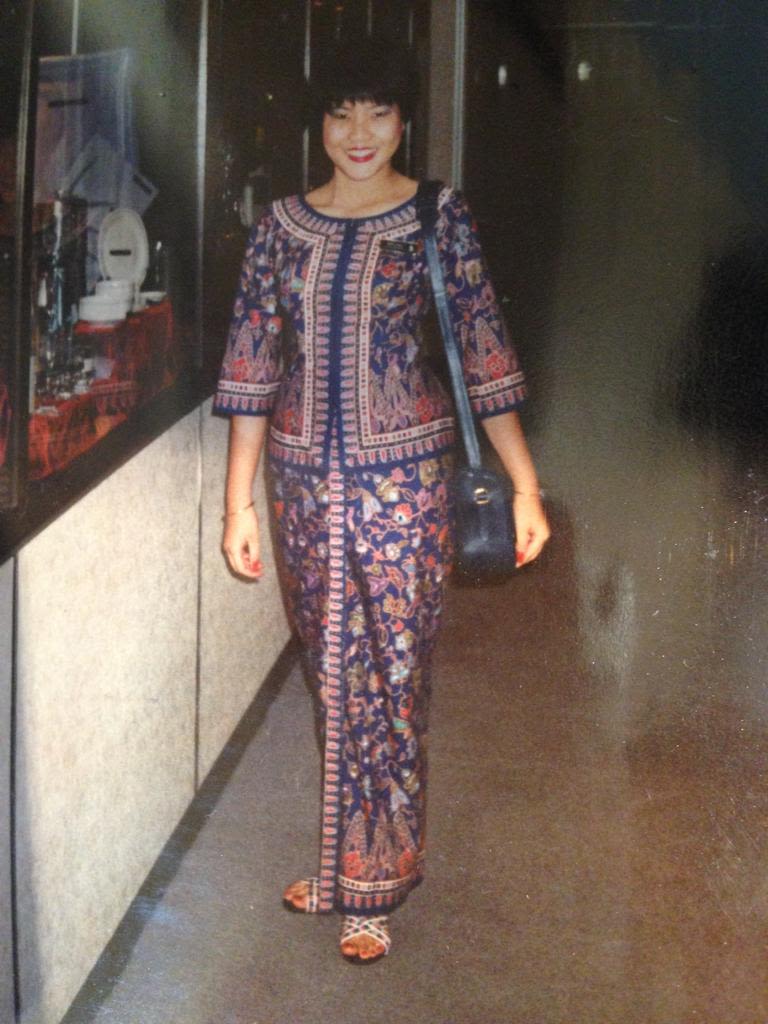

Polly Kuan's very first day wearing the sarong kebaya at SIA's old training centre in Paya Lebar, Singapore. Photo: Supplied.

Polly Kuan's very first day wearing the sarong kebaya at SIA's old training centre in Paya Lebar, Singapore. Photo: Supplied.

“It’s really enlightening to hear that [Singapore Airlines] are now allowing flying mums to fly,” Kuan says from her Melbourne home.

“It’ll be beneficial for the airlines, because as a mum myself I learnt so much about caring for infants onboard during emergency situations, especially on long-haul flights.”

— Polly Kuan, former SIA flight attendant

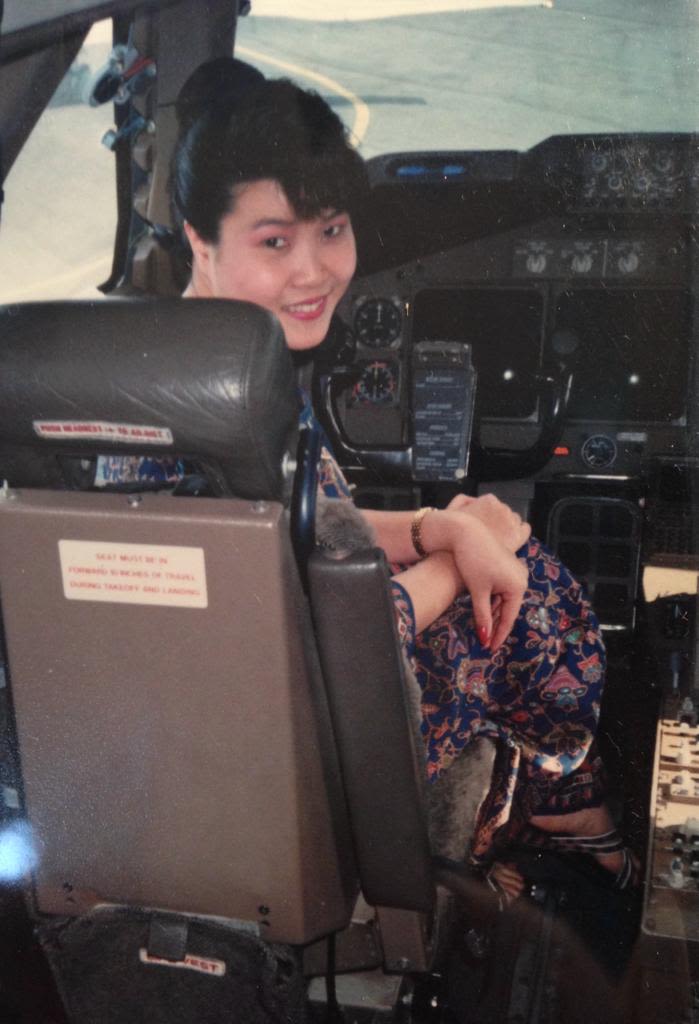

The height of Polly Kuan's bun rose with her rise through the ranks. Seated on the left-hand seat of 744-400. Photo: Supplied.

The height of Polly Kuan's bun rose with her rise through the ranks. Seated on the left-hand seat of 744-400. Photo: Supplied.

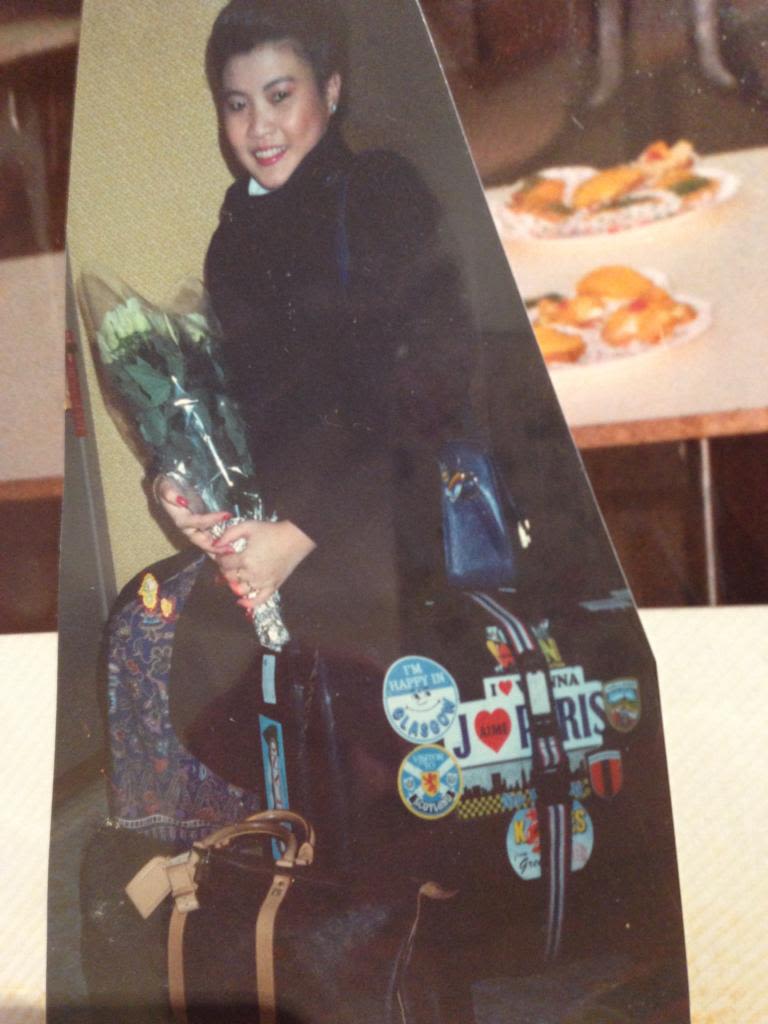

Polly Kuan on a flight from Paris. Photo: Supplied.

Polly Kuan on a flight from Paris. Photo: Supplied.

Polly Kuan training for SIA emergency procedures. Photo: Supplied.

Polly Kuan training for SIA emergency procedures. Photo: Supplied.

SIA’s trademark “Singapore Girl” image was born in the 1970s as the timeless face of Asian hospitality and service. And for five years, from age 18, Kuan lived what she saw as the dream of air hostess elegance.

But despite branding to suggest “she only gets better with age”, Kuan notes the shadow cast on her early days in the industry by the airline’s strict recruitment preferences for younger women.

“It wasn’t particularly pro-family in the sense that you had to be below 26 years of age and physically attractive in appearance,” she says.

“But just remember — to be a Singapore Girl is great. Every girl dreams of wearing the sarong kebaya.”

Now 52, the mother of one reflects fondly on the top-class training she received at the airline, and the standards which — despite their rigour — enabled its prestige.

“People in the West think because they’re cabin crew they can get into any airline. That’s wrong.

“It’s hard work to get into Singapore Airlines — it’s not easy,” Kuan says.

While she doesn’t regret her decision to leave the airline and consequent motherhood, she’s grateful Equal Employment Opportunity in Australia has given her a pathway back to her love of flying after a 20-year break from the industry.

“I’ve been very privileged in Australia. There’s no age limit here…I thought there'd be no way, because Singapore Airlines gave me the impression that I wouldn’t be able to do this job anymore.”

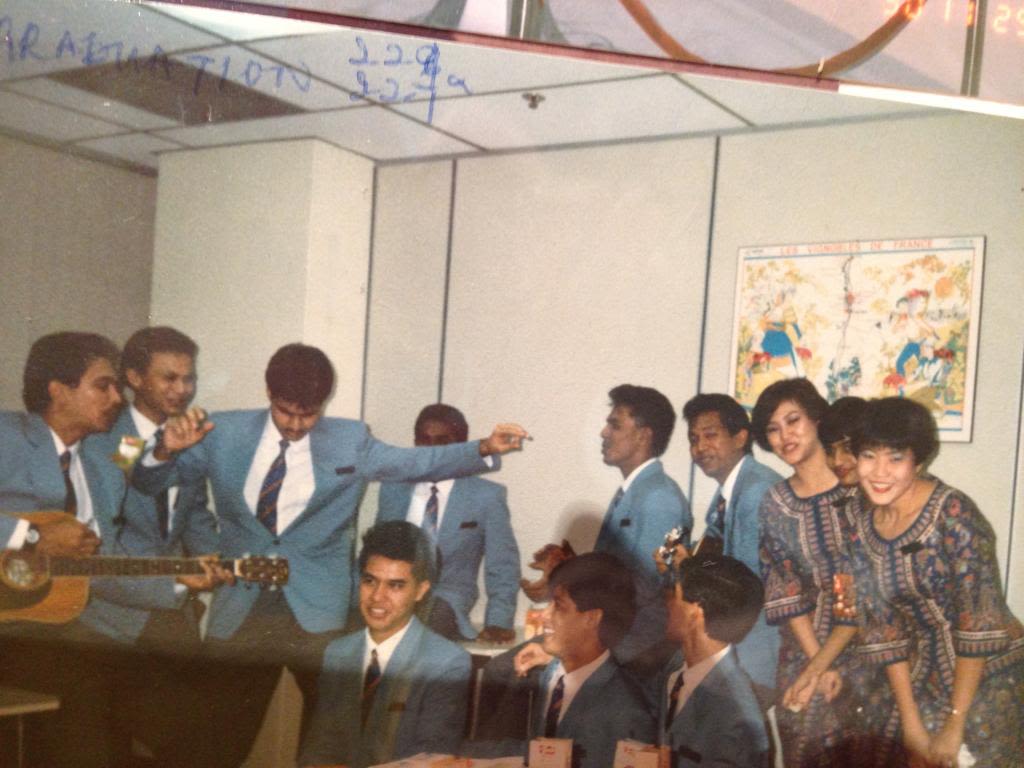

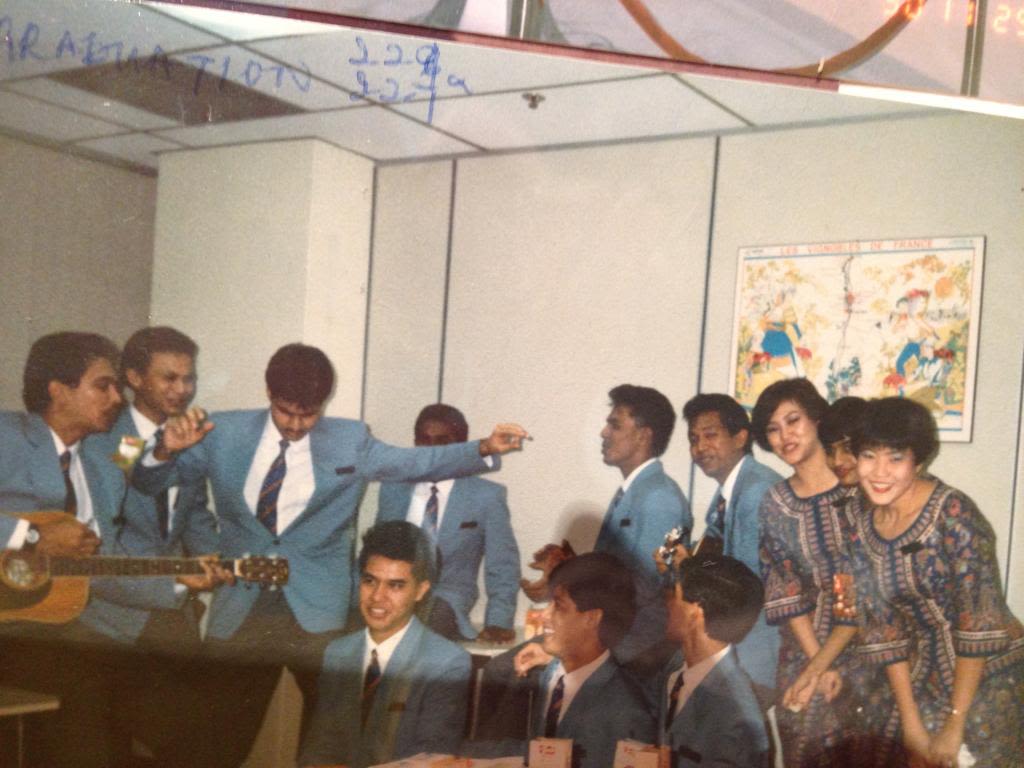

Polly Kuan's (pictured far right) graduation with the class of stewards and stewardesses. Photo: Supplied.

Polly Kuan's (pictured far right) graduation with the class of stewards and stewardesses. Photo: Supplied.

The new SIA policy gives expectant cabin crew the option of pursuing temporary grounded employment and 16 weeks of maternity leave before automatically being returned to the flight roster. But it’s a move which Singapore’s leading gender equality advocacy group believes is a decade behind the pulse.

In a statement to the media, the Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) described the airline’s previous policy as “absolutely unacceptable…discriminatory and sexist”.

“Looking beyond SIA, we know that maternity discrimination is still a widespread issue in Singapore, and that some employers do find ways to get around existing law,” the statement reads.

"Depriving women of the ability to work once they have children has long-term implications on their financial independence, retirement adequacy and personal fulfilment; the spectre of compromising their careers is likely what prevents many women from having kids in the first place. We hope that the forthcoming anti-discrimination legislation can clearly prohibit such practices."

...the spectre of compromising their careers is likely what prevents many women from having kids in the first place.

According to AWARE’s Workplace Harassment and Discrimination Advisory, there were 88 discrimination cases heard in Singapore in 2021. Of those, 81 per cent were maternity discrimination cases.

Legislation on women’s rights and development does seem to be on the government’s agenda. The Singaporean government published its first White Paper on women’s development in March this year, aiming to address discriminatory employment practices and enable flexible work arrangements.

In the outwardly progessive metropolis that is Singapore, women's policy is fresh on the government's agenda. Photo: Angela Ho.

In the outwardly progessive metropolis that is Singapore, women's policy is fresh on the government's agenda. Photo: Angela Ho.

Given Singapore’s tight labour market, Hays Technology commercial recruiter Sid Bhalla agrees the appetite for more flexible work-from-home arrangements is growing, and fast becoming the norm in an economy recovering from COVID.

“I find that if someone is given the leeway to be able to do their job from home while helping to look after their kid, there’s no problem.”

He says he is sympathetic to the pressure young mothers face to return to work.

“I have heard of situations where women have been forced to come back sooner than what they’d like to keep their jobs.

“It’s an unfortunate situation. I’m not saying all companies do it — I’m just saying that for women it’s tougher. It is a lot tougher.”

Born in Singapore and raised by maids, Bhalla’s own mother was back at work within a month of giving birth. He says he recognises more still needs to be done to support parents wanting to navigate a career while raising kids.

“There’s a lot of different factors to it…I think there still is a lot of work that needs to be done to help women and parents looking at childbearing before job opportunities.”

Local Singaporean Sid Bhalla recalls his childhood raised by maids. Video: Angela Ho.

Local Singaporean Sid Bhalla recalls his childhood raised by maids. Video: Angela Ho.

A mother’s choice of whether to spend time working or raising their child sometimes boils down to the finances required to sustain a household in one of the world’s most expensive cities. According to Mercer’s 2022 Cost of Living Index, Singapore ranked in at 8th most expensive city, meaning a return to work post-pregnancy is the reality most women face to ensure a dual income household.

This often involves enlisting the support of relatively inexpensive maids to mind their children while they plug back into the workplace.

Ari Rinastuti understands the demand for this service intimately, having been contracted to take care of a family’s two-month-old son and his brother.

“I can’t be a hypocrite,” she says, mindful of her own concerns as a mother of two boys.

“Maybe if there’s only one person working there wouldn’t be enough to support the [Singaporean] lifestyle. So you have to work.”

An Indonesian maid of four years, Rinastuti notes the way money plays a role in shaping the attitudes of certain career-focused mothers towards child raising.

“I’m not saying [every mother] is like this, but what’s in their minds is this — we’ve already paid for you to look after the child, so why don’t you do it?”

— Ari Rinastuti, Indonesian maid and mother

It’s an observation which local Singaporean teacher and mother Unitha Vasu also sees reflected in the parents she interacts with. The 37-year-old says her desire for independence and privacy meant she made the decision early on to be proactive in raising her now 10-year-old son Lohem. It’s a privilege she acknowledges not every mother has access to.

“I’m very blessed that I had the chance to be able to look after my son,” she says, reflecting on the decisions she made as a first-time mother at 27.

“It’s hard being a mother in Singapore — harder than most countries," she says.

“For me, I’m in a different place [financially], but I do believe that it is very tough for a lot of mothers out there.”

Vasu says the opportunity cost of spending 10 years looking after her son diverted her energy from making a difference out in the real world, where women now had the opportunity to do more with their lives.

Unitha Vasu recognises not all mothers have the choice of being as hands-on in motherhood as she was. Photo: Angela Ho.

Unitha Vasu recognises not all mothers have the choice of being as hands-on in motherhood as she was. Photo: Angela Ho.

The joys of motherhood surprised Unitha Vasu. Photo: Angela Ho.

The joys of motherhood surprised Unitha Vasu. Photo: Angela Ho.

Unitha Vasu recognises hands-on parenting is a privilege not all Singaporean mothers have access to. Video: Angela Ho.

Unitha Vasu recognises hands-on parenting is a privilege not all Singaporean mothers have access to. Video: Angela Ho.

In a Singapore experiencing its slowest decade of population growth since 1965, the population demographic is shifting. With these shifts come many independently-minded women grappling with their place in a Westernised society still dictated by milestones embedded in an Asian culture of feminine duty.

Further along the river’s bend on a starless Wednesday night at Boat Quay, 31-year-old Rua Chong stares up at the lights of the perpetually lit-up financial district and wonders what options she might have for raising a family in Singapore.

The tattoos banding around her upper arms are a window into a tension between contemporary self-expression and a conservative culture. A popular underground artist and musician, Chong pays the bills by reading tarot at glitzy expat bars, and shares the anxieties clouding her view of what a future in Singapore might hold.

“I worry. I do worry because now I’m in my thirties, and as much as I appreciate the life that I’ve lived…financially I’m very, very lost,” she admits, allowing rare access into a life which has for the better part of 31 years remained firmly offline.

“I would say for most people it almost looks impossible to be here for the long-term.”

— Rua Chong, working Singaporean woman

For Chong, desires to raise children fall secondary to the question of how she’ll navigate the spiralling cost of living in a culturally compressed and high-stress society.

She doesn’t have a solution. And she’s not alone at the crossroads.

For now, she hopes the problem will find a way to resolve itself with time — a common refrain when the way forward isn't clear. The cultural conversations around the "Singapore Girl" continue, and young Asian Australian women watch with interest.

At some point, even if it never feels like it, the lights of the towering totems of Singapore also take a break, and the night breathes on once more.